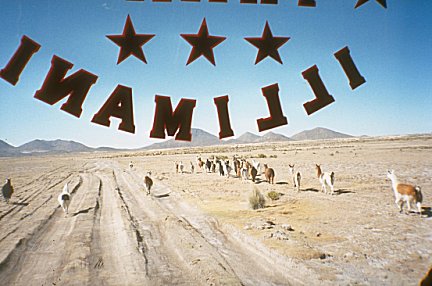

Into the Altiplano

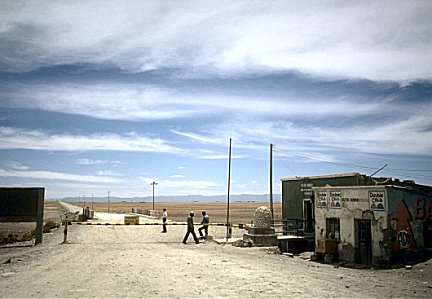

[Photo ©Mary O'Connors] We left La Paz, Bolivia's capital, in a bus. At first we drove on asphalt roads through arid countryside, with cultivated fields that looked just like raked gravel. We passed many Aymará Indians, who make up most of Bolivia's population. Although the men look very modern in their sneakers and jeans, most of the women were traditionally dressed in derby hats, flaring multi-layered skirts, and brilliantly colored shawls. We stopped at several barricaded police checkpoints. Each checkpoint had a shrine, nominally Catholic but with clear animist themes. At one such checkpoint we bought bananas and cookies in the surrounding village while our drivers negotiated with the police. Later, when the food ran short, we'd be very glad of these little extravagances.

We had two possible destinations: one was Rio Mulatos, where the Bolivian government had staked out rows of tiny compounds in the desert, The other was Challacota, a remote village many miles northwest of Rio Mulatos. Rio Mulatos would be crowded and unpleasant, but Challacota was very remote and with no facilities at all. The decision: we would go to Challacota. Our guide was confident that he could find it. From the drab town of Oruro we took the road that led southwest into the desert.

Day of the Dead

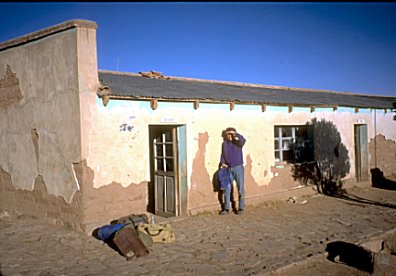

To the right is the home where we joined a Day of the Dead celebration.

This day was Dia de los Muertos, Day of the Dead, when Bolivians pay homage to the departed. An elderly Cholo in a nearby adobe hut invited us to join his family. We entered his one-room home, stooping under the low ceiling. One end of the room was occupied by a beautifully made shrine, a table laden with chickens, fruits, wreaths, loaves of bread, packs of cigarettes, and coca leaves all carefully arranged around the candles which provided the room's only light. Several old men sat on rough benches against the other three walls, dignified but friendly. Our host offered us beer and explained, through gestures, that we were honoring his departed wife. We reluctantly said our thanks and farewells, and soon we were out on the great flat plain. A deep blue sky towering over us, filled with dramatic cloudscapes. The land, improbably, became even drier. We saw no more agriculture, passing only an occasional herd of sheep, alpacas, or llamas. We saw not a single tree, only a scattering of low brush on the red dust. Sometimes we passed a single Indian afoot or on bicycle, incongruous in the vastness. The road soon became a pair of ruts in the red dust. And when we crossed a dry watercourse or salt flat, the ruts disappeared entirely. Once we forded a small stream, after the drivers threw stones into the water to gauge the depth. Occasionally we followed the wrong ruts and had to backtrack to find the actual road. Our driver became worried about our location. He had been trying to contact his agency in La Paz by radio. Our schedule was tight, for we had to reach Challacota by sundown. We were hungry, and our guide promised that an advance group awaited us in Challacota with T-bone steaks.

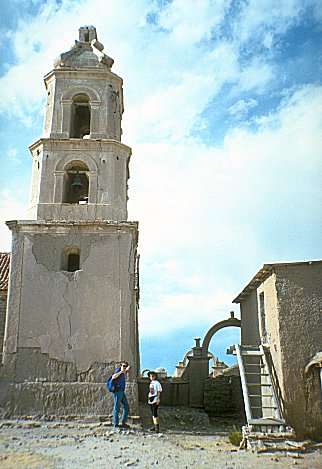

We passed a few dusty adobe villages, each with a church, a blue-painted school, and, surprisingly, a basketball court. Many of the buildings were abandoned and in ruin. We stopped near one such village so the driver could ask a solitary bicyclist for directions. His advice did not agree with the radioed instructions from La Paz. Our guides debated among themselves, consulting several different maps. We drove on, nervously scanning the horizon and watching the sun's steady descent. We were lost.

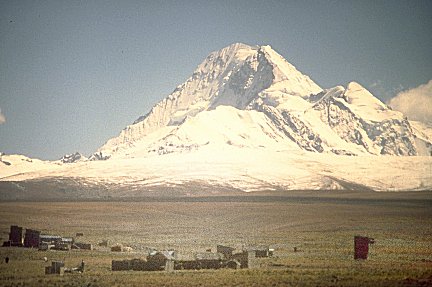

The Wrong AndamarcaDust devils spun continuously on the horizon. We were now near the largest salt flats in the world, the Salar de Uyuni. Beyond those flats, to the west, lies the Atacama in Chile, the driest place on earth, where no rain has ever fallen in recorded history. We could see the snow-clad peaks of the Occidental Real floating in the distant east.

We stopped at another village to ask directions but found no-one. We wandered past the church into the open Altiplano and saw a crowd of people celebrating Dia de los Muertos in the cemetery. As we approached, they beckoned us to join them. One thoroughly-drunk young man offered us a liquor which he poured into plastic cups from a large green plastic jerrycan. It tasted very good, like mezcal, but I soon found myself trying to explain, in English, why I must refuse a second cup while he eloquently argued, in Spanish, why I should drink more. The villagers insisted that we were many miles from the correct route. But whenever the sputtering radio made connection, La Paz insisted that we were still on course. At last we left the village, still trusting the La Paz radio. The sun was close to the horizon, and we had to hurry to reach our destination before nightfall -- driving in darkness would be foolish in this terrain. We passed some low hills, each one topped with a small stone silo-shaped structure. Our guide explained that these are ancient Aymará tombs, never excavated, and carefully avoided by the living.

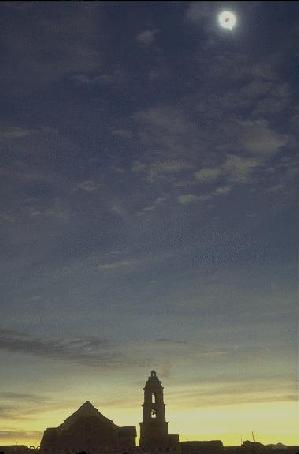

Soon after, we reached Andamarca. But it was the wrong Andamarca! The road, such as it was, ended here. Our driver at last discovered that our route should have been through Belen de Andamarca, many miles to the west, not here in Andamarca de Santiago. The locals had been right all along. It was twilight, and we could go no further. Worse, our dinner was in Challacota. We had been on the road for fourteen hours. The locals were surprised at our presence, and someone told us that the village had never before seen foreign visitors. This was a bit hard to believe, since the colonial church whose bell tower overlooked the schoolyard was dated 1728. Our guide negotiated with a local official and arranged for us to sleep in the school compound. The school had three classrooms with adobe floors thick with dust. Many of the windowpanes were broken. We moved the wooden benches up against a wall and lit candles against the deepening darkness, for Andamarca has no electricity. The outhouse toilets were squat-style, holes in the ground straddled by two concrete tiles to stand on.

Our guides found some chickens and rice and started to make a dinner. Someone started a brushwood fire in the schoolyard. Someone else discovered a small shop across the street which usually operated on the barter principle, but was willing to accept our bolivianos in exchange for beer. At this elevation the freshly-opened beer foamed ceaselessly, but it tasted wonderful. The stars came out, and in the absence of electric lights and at this altitude, they blazed with knife-edged brilliance. Four or five young men of the village joined us, and we shared our beer with them as we stood around the fire. One of them, inspired, told us that they would play us some of their music. They left to fetch, we thought, their instruments, and we eagerly anticipated hearing some of the beautiful, heartbreaking Andean music. But when they returned, one of the young men proudly held a cheap boombox playing syntho-pop music! After some negotiation, we prevailed on them to play a tape of indigenous music, and soon they were teaching us dance steps, and under those stars, with the eddying sparks from the fire, warmed by the beer, we danced.

Challacota

Yes, we did reach the eclipse. We hired a local boy to guide us, and we departed. At first we retraced our route past the Aymará tombs, but soon we turned westward. The road became yet worse, and sometimes we were surrounded by Saharan sand dunes. Vicunas, so graceful compared to the ungainly llamas, occasionally bounded across our path. The weather was ambiguous. We saw storms in the distance and massive cloud formations above us. We'd be crushed if we came all this way and couldn't see the eclipse because of bad weather. We passed through Belen de Andamarca, dropped our guide off with his bicycle, and hired two young brothers to take us on to Challacota. Challacota was much smaller than Andamarca, and seemed mostly to be in ruins. This town looked like seven- or eight-hundred people may once have lived here, but now there couldn't be more than fifty. Challacota is surrounded by salt flats stretching out toward distant mountains. Again, we stayed at the local school. This had only a small one-room adobe schoolhouse, so we set up tents in the schoolyard.

Barbara and I wandered to the local cemetery with Nike, who speaks fluent

Spanish. We talked with some Aymará women. Nike asked how they felt about

tomorrow's eclipse, and one responded that normally they'd be worried,

but were reassured because American scientists were there to make sure

everything went alright.

As the sun began to set, Barbara organized a basketball game with the American and Aymará women. The Aymará women doffed their bowler hats and played with a surprising skill. They are not tall, but they handled the ball well and were very fast, with their long braids flying behind them. And their endurance showed us why the Bolivian national soccer team, whose home stadium is in La Paz at 12,000 feet elevation, has never lost a home game. The promised dinner of T-bone steaks turned out to be tough slabs of some unidentifiable gristle served with rice and boiled potatoes. There was no sauce and no spices. As hungry as we were, it was still difficult to choke down this dry, flavorless stuff. That night in our tent, we vainly tried to sleep, but all night long we heard our worried co-travelers mutter about the weather as they observed the darkened heavens. In the morning we climbed out of our tent to view a threatening sky.

After breakfast our group carried the astronomical paraphernalia out

onto the soccer field, where the salt crystals crunched underfoot. There

were breaks in the clouds; there was cause for hope.

The Eclipse

It is impossible to describe a total eclipse of the sun. It is an event so awesome, so overwhelming, that people will endure hardship and discomfort just to observe it. We were not astronomers, we were just there for the experience. The sky cleared, and the eclipse exceeded all our expectations. (See the Eclipse FAQ for a discussion of the effects of a total eclipse.) People shouted and wept. The Aymarás kneeled, averted their eyes from the solar disc, and prayed. After the eclipse, we packed up our gear while warmth and light returned to the world. (The temperature had dropped from 60 degrees Fahrenheit to less than 40 within about five minutes.) By nine o'clock we were on the bus again, lurching northward on two ruts in the red dust, trying to reach La Paz by nightfall. And we had a new worry. The clouds were menacing, and we saw storms on the horizon. This entire region is inaccessible during the rainy season, which was due to begin now.

Another problem was that we were traveling by a different route, the route we should have taken from La Paz to Challacota. With no guide, we risked losing our way again. Through the long day we drove, through occasional spatters of rain. We stopped once, when the bus got stuck in the thick red dust of a wide dry river flat, and all got out to push the bus free. As the afternoon wore away, the road began to improve, and we recognized landmarks. As dusk fell, we cheered and applauded our driver as we finally reached the first paved road we'd seen in three days. At ten o'clock we reached our hotel in La Paz, where the proprietors had set out hot coca tea for us. And after three days without bathing, I really enjoyed the luxury of a tepid shower!

Appendicitis

We finally got to bed around 1:00 AM, and woke again at 5:00 to take a trip to Cuzco, Peru. We had spent three days with an organized tour; now we would spend the rest of our trip on our own. Several days later, things took an ugly turn: I got sick. In spite of this, we flew to Sucre, Bolivia. Sucre is an absolutely charming city of around 100,000 people. At 9,000 feet elevation, oxygen is gloriously abundant. We stayed in the Hotel Colonial, on the town square. I got sicker, with intestinal bleeding, and finally we called a local doctor. The South America Handbook recommended Dr. Gastón Delgadillo Lora, so Barbara phoned him. He came directly to our hotel and became quite worried; I had an inflamed appendix and might need an appendectomy. After tests, he came back in the afternoon with the diagnosis of Salmonella food poisoning. Dr. Gastón, as we came to call him, spoke excellent English, although he said he was more comfortable with French or German. He visited our hotel room three times a day for three days. At each visit he gave me huge injections of antibiotics and anti-inflammatories. He stayed an hour each time, to make sure I didn't have adverse reactions. We discussed philosophy, music, history, and travel. He helped Barbara change our tickets at the local airline office, and helped order food when I could eat again. His final charge for all this work was $500.00, and he doubtless would have lowered it if we had shown the slightest hesitance! He told us that he had traveled to New York, and he knew what it was like to be a stranger in a strange city. We corresponded for many years with the wonderful Dr. Gastón and hope to visit him and his lovely city again someday. We flew back to La Paz for one more day and night before returning home. |

Dharma

Dharma